"Portage, Ragged Lake Spring" was selected for Creative Scene Investigation due to its similarity with Tom Thomson's "Spring Break-up, 1916". The story of the painting can be found in the lines within the ice. Interesting science and natural history can be discovered in both of these paintings.

Within an "oeuvre", the artist can go through distinct creative phases determined by the colours on their palette, how they handle the brush and even the subject matter they select. With these two paintings, the subject was the characteristics of ice in spring. Recall that an artist's oeuvre is their total body of work over a lifetime. "Oeuvre" can also refer to a single work of art. Thomson painted for less than five years and his "oeuvre" evolved rapidly during this brief flash of creativity.

Similarly, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) "

oeuvre" only spans a decade. His work grew steadily brighter after 1886 when he went to Paris and lived with his brother Theo. Vincent made new artist friends in the "

City of Lights" including John Peter Russell, Émile Bernard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Signac and Paul Gauguin. The friends regularly wrote to each other and exchanged paintings and self-portraits. Vincent applied brighter colours with short brush strokes. He admired the work of his new friends but developed his own style which would become known as Post-Impressionism.

Surprisingly, Tom Thomson (1877-1917) was still feeling his way artistically. Although he greatly benefited from his friendship with his coworkers from The Grip, his work really soared after 1914 when World War One turned him into a solitary artist. Tom developed his own style in isolation surrounded by nature. It is not surprising that he is often called "Canada's Van Gogh".

Now back to the Creative Scene Investigation. The colours and handling of rotten and melting ice are similar between "Spring Break-up" and "Portage, Ragged Lake Spring". One might suspect that they were done at the same time, notably in the spring of 1916 when Thomson had those particular colours on his palette and was painting similar subject matter. It would have been most helpful if Tom had left a few notes or had a brother like Theo Van Gogh.

|

Portage, Ragged Lake

Spring 1915

Oil on wood 8 7/16 x 10 9/16 in. (21.5 x 26.8 cm)

Tom's Paint Box Size

Catalogue 1915.08

|

The Tom Thomson Catalogue Raisonné dates "Portage, Ragged Lake Spring" from 1915 while the National Gallery suggests it was painted in 1917. The handling of the icy subject matter and colours suggest that 1916 is even a possibility. That assumes of course that "Spring Break-up" was indeed painted in 1916! Even expert art historians are unsure of when "Portage, Ragged Lake Spring" was painted. The following Creative Scene Investigation might offer some further insights.

My Thomson friend observes:

"I'd guess not 1916, since he probably wouldn't have had time for a canoe outing to Ragged Lake before heading to the Cauchon Lakes (assuming he was at Canoe Lake prior to the fishing trip). Unless, perhaps, there was a road to that location - I'll have to check on that. The colours do remind me of "Spring Break-up" but there is also one from 1917 called Winter Scene (catalogue raisonne 1917.07) which is also reminiscent of both. We'll have to chew on that a bit."

As my Thomson friend asserts:

"Anyway, I have a tentative location for the painting."

My Thomson friend feels that the painting location was located at what is now a campsite at the south end of Smoke Lake looking eastward toward the start of the portage up to Ragged Lake. See Maps by Jeff for complete details. The yellow star in the following graphic suggests that the "view would have been east across the little point towards the far shore."

As depicted in the following graphic, the terrain does match well between the location my Thomson friend suggested and the entrance to the portage to Ragged Lake.

Now for the weather. I consulted with my friend Johnny Met and he saw the following in the small sliver of sky at the top of the panel:

"The clue is looking eastwards. I think it is sunrise. I have seen lots of sunrises starting clear and then middle cloud forming quickly and then a few showers. One of the guys at the weather centre called it morning madness. In this case, Tom did a lot of painting in the foreground, looking like logs and trees."

Johnny has a lifetime of experience observing the weather. He has seen it all before - many times over. The skies were certainly overcast with nil cloud structure to be discerned. The cloud type was altostratus. Looking eastward, the rising sun would have only been a dimly visible orb through that layer of cloud. A warm conveyor belt is a classic explanation for what Tom painted and Johnny observed.

The following graphic places Thomson within the typical parade of weather systems. Altostratus (AS) is typical of the anticyclonic companion of the warm conveyor belt. The air actually descends in that stable portion of the flow and precipitation is unlikely. The cloud transforms into altocumulus (AC) as the warm conveyor belt advances across the painting location. The cyclonic companion of the warm conveyor belt is more unstable with ascending air. Altocumulus castellanus (ACC) is common in this region of the weather system and can produce the showers that Johnny mentioned. Tom's position either north or south of the surface warm front (the red line with bumps) could even be determined if we could decipher the wind direction. For example, a southerly breeze would have placed him within the warm sector of the weather system and south of the warm front.

As much as I love the weather, Thomson only devoted a small portion of cloudy skies to the panel. The weather was not his subject on that particular day. The ice patterns in the bay of the south end of Smoke Lake were the real source of inspiration for Thomson. Most people would not even see the interesting shapes that so intrigued Thomson. The real story behind "Portage, Ragged Lake" can be found in the ice. I doubt if he changed the orientation of those lines at all. Tom painted exactly what he saw which allows us to interpret the science behind his art. Please read on and let me explain.

The story actually starts at the end of the last ice age 20,000 years ago. Glacial meltwater from what would become Ragged Lake carved the shapes that would evolve into the southern basin of Smoke Lake. The following graphic will save a lot of words.

The same process that shaped the southern basin of Smoke Lake also sculpted the ice that Thomson observed. The following graphic will save some more words and hopefully still explain the science.

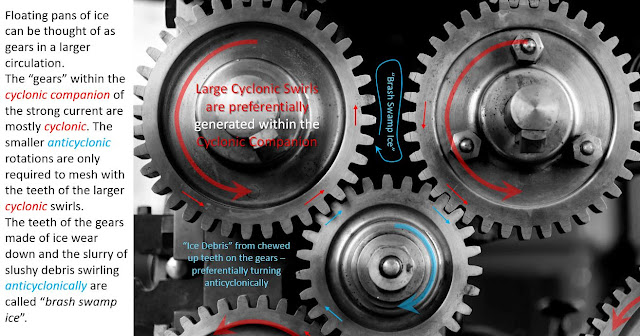

When I taught meteorology, I would try various approaches, graphics and analogies in an attempt to reach as many participants as possible. Everyone has their own, unique and favourite ways to learn and assimilate new concepts. The following graphics are examples of different ways to look at the ice pans that Thomson observed.

I always found the satellite view to be easier to comprehend. Please employ your Coriolis hand (right hand in the northern hemisphere) to make sense of the nested rotations.

Out of necessity, the above graphics must display the swirls as planar, flat entities. But the swirls represent three-dimensional vortices that extend through the depths of the water, driven by the three-dimensional spring current surging down 16 metres from the level of Ragged Lake. This current drives the gyres in the south end of Smoke Lake in the same way that the jet stream energizes the conveyor belts of storms in the atmosphere. Fluids are full of surprises and interesting patterns.

Ice integrates forces and motions over time. These shapes are captured when the temperature drops below freezing - typically overnight. These forces are applicable at all time and space scales.

Ice circles can be hundreds of metres across with a scale determined by the geography of the waterway.

An underlying structure can typically be discovered in what might appear to be chaos. We just have to slow down and look for it. That is something that Tom Thomson did with half of his little panel focused on patterns in the ice. The hard-working loggers and rangers did not have time to see the beauty in those designs of nature.

As well, the colour of the ice takes on that of the water from which it is created. Algonquin is the important source of five major Ontario rivers. The swamps and bogs which capture the rain and snow are nutrient deficient. Organic decay in these headwaters produces tannins and the characteristic tea colour of the water emerging from the Algonquin Highlands. That same water forms the ice and that is why Thomson selected the colours that he did!

There is even more to the story of "Portage, Ragged Lake"... There are a lot of questions about how and when Thomson might have made that trip. Given the extent of the ice Tom observed, paddling the 9 or 10 kilometres from the Canoe Lake dock was certainly not an option.

The logging camp probably dates from the days when Gilmore and Company were active around Canoe Lake - namely 1897 to 1901. The Shelter Hut was probably built after 1893 when Algonquin Park was established. The exact dates for these structures are unknown.

As my Thomson friend observes:

"I would guess that TT most probably just hiked down there, did the sketch (or perhaps sketches, there and some other spots along the way) and eventually hiked back to his comfortable room and Annie Fraser's good meals at Mowat Lodge. I can't imagine the accommodation in a lumber camp shanty of the era would be all that appealing - things were pretty cramped. The meals would have been hearty but probably not up to Annie's standard, and I don't know how much they would have had to spare for some unknown person who just dropped in. All the supplies would have been brought in the previous fall, with quantities calculated according to the number of men in the camp...

I don't know what the reaction would have been if some random unknown artist just showed up at a shanty door looking for a bed and/or a meal."

Algonquin Park personality Ralph Bice from Kearney, (1900-1997) was a trapper and writer who disparaged Tom Thomson and his artist friends saying "that unless you were out working or logging, you weren't much thought of..." Bice branded Thomson as a "drunk" who probably fell out of his canoe and died by accident or killed himself in a bout of depression. Bice was just seventeen when Thomson died. Ironically, both Tom and Ralph are honoured with Algonquin Park lakes named after them...

Further, my Thomson friend observes:

"I am beginning to think that perhaps 1915 is not an unrealistic date. The provenance indicates MacCallum was the first owner and then it was a bequest to the National Gallery. It seems reasonable that he might perhaps have seen this sketch during a visit to Tom's shack in late 1915 or early 1916 and, having recognized the quality of the sketch, acquired it for his own collection. If this was the case, it would have been easy for him to ask for the identity of the location."

|

Portage, Ragged Lake

Spring 1915

|

The back of the panel also hints at the possible story behind this painting. That tale might have even unfolded in the Studio Building when Harris or MacDonald were sorting through the stack of panels salvaged from Thomson's Shack. Someone had written "

Spring" on the back of the panel as the tentative title. That title was "

crossed out" and replaced with the following.

"Portage Ragged Lake / 27. / James M. MacCallum"

Note that "National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (4712)" also appears on the back of the panel appended to the above text. Those words would have been written when the gallery obtained the sketch from MacCallum to denote the acquisition number in 1944.

An image of the actual back of the panel might yield more information. Perhaps the nondescript title "Spring" was crossed out upon the advice of someone who actually had been to that location with Tom Thomson or had asked him about the painting as suggested above. That person would have been much better qualified to name the painting. The question is who? The best guess is that it was Dr. MacCallum.

As co-owner of the Studio Building with Harris, MacCallum would have been a frequent visitor to where Thomson's paintings were being organized. MacCallum might have even been very involved with the parsing of Thomson's oeuvre. MacCallum certainly took more than a passing interest in Thomson's art having sponsored him starting in the fall of 1913. He also offered the same support for a year to A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974). The rest is art history.

MacCallum may have witnessed the painting being processed as "Spring" and saved the panel the further indignity of the Estate Stamp. Of course, like many if not most other things about Thomson, we will never know for sure.

Inscription:

- verso: u.l., in black crayon, 25;

- c., H.M.L. 84 (circled);

- l.l., label, Spring (crossed out) Portage Ragged Lake / 27. / James M. MacCallum National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (4712)

Provenance:

- Dr. J.M. MacCallum, Toronto

- National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (4712).

- Bequest of Dr. J.M. MacCallum, Toronto, 1944

"H.M.L." written on the back of this panel is another unknown. The immediate guess was that it referred to one of the Laidlaw brothers who were early collectors of Thomson paintings on the advice of their mutual friend Lawren Harris. But their initials are "W.C." and "R.A." so the text is still undetermined unless there are other Laidlaws with "H.M." initials. None of that mattered anyway as MacCallum snagged the painting for his own Thomson collection.

In many ways, "Portage, Ragged Lake" is the quintessential Thomson painting - a simple observation of the beauty found in natural shapes and colours that most people ignore. The unpretentious brushstrokes belied much deeper levels of science and natural history that are required to complete the story. Of course, you can simply just appreciate Thomson's art and that is OK too!

Thank you for taking the time to read this...

Warmest regards and keep your paddle in the water,

Phil Chadwick, Tom Thomson Post TT-131