Tom woke up with a start at sunrise on Monday, May 24th, 2015. The sunrise light coming in the window of his second-story room at Mowat Lodge was most unusual. The colours were unlike anything he had seen before. Tom grabbed his paint box and hurried to the shore of Canoe Lake to make a weather observation... but I am getting way ahead of myself. Please let me explain.

|

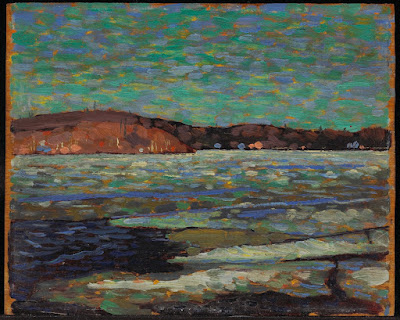

| Sunset Alternate title: Sunset II Summer 1915 Oil on wood panel 8 3/8 x 10 1/2 in. (21.3 x 26.7 cm) Tom's Paint Box Size |

Sometimes Creative Scene Investigation can be challenging. It is important to keep one's mind open to the obvious facts even if written history says otherwise. The puzzle pieces must be carefully assembled to complete the picture. The obvious preconceived solution to this painting had to be reconsidered from the ground up (so to speak) to solve this painting.

J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris met in the Studio Building in the spring of 1918. Tom's paintings from the Shack had been stacked in the Studio Building. Harris and MacDonald planned to sort through Tom's art, make comments on the back and distribute what they felt were the best examples of his genius. "Sunset, Alternate title: Sunset II" was one of those panels and displays the distinctive "TT Estate Stamp". They were correct about the quality of the art but missed the real story behind this painting.

At first glance, the strong sky colours were characteristically bright and bold like "sunset". The distant shore and ridges were devoid of colour as one would expect in the evening. Tom was certainly looking toward the sun but was the sun really setting as both the title and alternate title suggest?

The clouds were very rich hues of pink, orange and red. The cloud-free areas were even yellow and green. There was no blue to be seen in that sky at all! Some of Tom's friends suggested that he was greatly exaggerating his Algonquin colours. I think not and can explain why.

The clincher in understanding this painting is to first establish the location and direction of view. The far shore of the lake was very dark and devoid of colour suggesting strongly that it was back-lit. The sun had to be behind those hills. As a result, if this was sunset, Tom had to be looking west. But let us consider what the terrain was saying.

Matching the hills and ridges in Tom's painting to those of the Canoe Lake terrain map suggests that Tom was actually looking east-southeastward across the northern basin of Canoe Lake.

Further corroborating evidence can be discovered by comparing other Thomson paintings of the eastern shore of Canoe Lake. The similarities in the silhouettes of the distant forest and hills are unmistakable. The following graphic compares two paintings completed on very different days in 1915 but both exhibit the same details. Tom was looking eastward at a rising sun that morning.

Everything about this painting screams it as a sunset observation. J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris reacted as most people would and dubbed it as an obvious "sunset" painting in the spring of 1918. The sky was ablaze with typical sunset colours. Other paintings from 1915 and even 1916 use similar colours and they were painted at sunset. See Tom Thomson's "Sunset" 1915 and Tom Thomson's Spring Sunset, Algonquin Park Spring 1916 as just a few examples of Tom's colour choices. How can this work be anything else but a sunset? It takes a volcanic eruption in northern California to provide the answer to that question.

Creative Scene Investigation suggested the timing of this painting as May 24th, 1915, two days after the eruption of Lassen Peak. It takes a couple of days to spread the sulphate aerosols from northern California to eastern North America. In addition, Tom did not like to paint while being bitten by ferocious black flies which typically start feasting in the last week of May - although Tom likely would have made an exception and endured the bugs given this inspirational sunrise.

The following graphic greatly exaggerates the scales to explain the optics of this sunrise. The graphic is viewed looking down at the rotating Earth from the vantage of the North Pole. From the Earthly perspective, the sun rises over the eastern horizon as the Earth itself spins. The direct beam of light from the sun 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away passes through a long path of atmosphere before illuminating the scene. Rayleigh scattering by atmospheric molecules and the tiny volcanic sulphate aerosols remove the blue wavelengths from the beam. The blue light is Rayleigh scattered in all directions. The remaining longer wavelengths of light illuminate the clouds comprised of much larger particles. Mie scattering efficiently distributes the green, yellow and red light in a forward direction to any observer who might be watching - in this situation, it was Tom Thomson.

The colours that Tom observed and recorded are explained in the following graphic in terms of Rayleigh and Mie scattering. The yellow and green cloud-free portions of the sky resulted from some aerosols being a bit larger than atmospheric molecules and thus scattering longer wavelengths like green and yellow. The blue wavelengths from the sun had already been scattered out of the beam.

|

| Satellite View Looking down on the Conveyor Belt Conceptual Model. Thomson was located near the leading edge of the warm conveyor belt (WCB) looking easterly at the sunrise. |

|

| A similar warm conveyor belt with brighter sunrise colours. Science can be beautiful. |

This painting was from the spring of 1915 before the biting bugs emerged.... it was probably just a few days after May 22nd, 1915 in fact - I am guessing that May 24th was the exact date but it is possible. That forecast was based on sulphate aerosols, volcanic ash and bugs. Thomson spent his summers fishing anyway.

This painting really needs to be renamed as something like "Brilliant Spring Sunrise after Lassen Peak". Thomson would not have heard about the California volcanic eruption while in the backwoods of Algonquin so that part would not have appeared in any title. However, something is needed to distinguish this from the other sunrise paintings. That also explains why I supplement the name of my art with a chronological number which has to be unique.

|

| Sunset Alternate title: Sunset II Summer 1915 Oil on wood panel 8 3/8 x 10 1/2 in. (21.3 x 26.7 cm) Tom's Paint Box Size |

What motivated Tom to record this weather observation? Tom must have been shocked to see the colours of the sunrise reaching into his bedroom window. I can imagine Tom grabbing his paint box and rushing out to the shore of Canoe Lake to chase the sunrise light before it disappeared. That is why artists paint... we all chase the light in amazement at the beauty of nature ... and the weather. The warm conveyor belt was probably headed northeastward and the bulk of the weather would have missed Canoe Lake.

Tom might not have understood all of the science and would certainly have not known that Lassen's Peak had just exploded - but he was truthful to what he saw. In that way, the science must also be accurate. Tom was amazed by the light streaming into his bedroom window. Tom was also a morning person... let's get going with the sun. Rise and shine.

No one can say when, but it is certain that Lassen Peak will experience volcanic eruptions again. Volcanologists know that the 1915 eruption occurred after a dormancy of about 27,000 years so do not expect the next eruption anytime soon although it could be tomorrow.

Inscription recto:

- l.r., estate stamp

- c., estate stamp;

- u.l., in graphite, Sunset;

- in graphite, u.r.q., Reserved – Mackenzie[sic];

- in graphite,

- l.r., No. 29 (19?) Mrs. Harkness / Mrs. Williams McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg (1966.16.69)

- Estate of the artist

- Elizabeth Thomson Harkness, Annan and Owen Sound

- S.J. Williams, Kitchener, Ontario, 1926

- Mrs. S.J. Williams, Preston, Ontario, by 1937

- Esther Williams, Preston and Toronto by 1941

- Laing Galleries, Toronto, 1960?

- Robert and Signe McMichael, Kleinburg

- McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg (1966.16.69).

- Gift of the founders, Robert and Signe McMichael, 1966

Why does any of this science matter? The magic of nature which is described by science was certainly important to Thomson. To omit this information in any investigation of Thomson's art is to ignore the essence of the man. Just sayin'.

Warmest regards and keep your paddle in the water,