Aside from the stated justifications for these blogs as included in "Tom Thomson Was A Weatherman - Summary As of Now", there are some personal reasons why considerable effort is put into turning the draft Thomson book into a Blog. I am obsessed with learning - mostly focussed on the "nature of things" (Thank you David Suzuki) but really, anything is fair game. This endeavour helps to keep my meteorology sharp… use it or lose it.

The Tom Thomson experts that I know are a wealth of knowledge - something that became more obvious when the concept of this "Artist's Camp" blog was germinating. The weather in this painting is a patch of stable altostratus. That cloud was important to Tom as he included it with some difficulty behind the screen of trees. There are a few possible explanations for why that front-lit cloud was there but I will only depict the most likely below. The really interesting information comes from my Thomson friends.

On one occasion when I presented in Algonquin Park, September 1st, 2017, the staff had Tom’s tent set up in the Visitors Centre. I took a bunch of pictures and recorded the story behind Tom’s tent for my notes. It was thrilling to see his actual tent. The "balloon silk" was no longer white but the provenance of the tent via Tom's friend Ranger Thomas Wattie of South River is very convincing.After selling a few paintings (including $500 from the sale of Northern River to the National Gallery in 1915) and with some money coming in, Tom went shopping in the summer of 1915. He did not have access to the materials we enjoy for lightweight canoe tripping a century later. Fibreglass, kevlar and especially carbon canoes were not even a dream back then. Tom's canoeing adventures were decades before LED lanterns, water purifying kits, and a multitude of inventions that modern trippers deem essential. After all, every item had to be carried across the portage and I doubt if even Tom thought that portaging was fun…Tom wanted light and state-of-the-art gear (for 1915 at least)!

In late July or early August, 1915 Tom bought his new 16-foot Chestnut Guide Cruiser canoe, silk tent and other essential camping supplies. Tom used a $2 tube of cobalt blue oils with a standard marine grey to make his canoe truly unique. The "dove grey” colour would stand out from all of the traditional red and green canoes used by the lodges.

|

Tom paddled out from Canoe Lake on a long trip that likely went to the Magnetawan River, coming out at South River around Labour Day. Thomson then joined J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) at MacCallum’s cottage on Go Home Bay to measure the walls for a series of seven commissioned decorative panels. Tom then returned to the park, where he remained until the weather drove him back to Toronto at the end of November.

Given the autumn colours, this painting would have been painted in October or early November before his return to the big city - back then the big smoke of Hogtown was Toronto the Good before it became Hollywood North.

Thomson painted at least four images of his beloved tent. The following graphic includes the other three paintings of his brand-new silk tent.

At this point, I asked one of my Thomson friends to weigh in:"The Artist's Camp has such a nice feeling to it - it makes me feel that I'd like to be there... One vivid memory is lying awake in the middle of the night with a full moon casting shadows of leaves on the tent - lovely. I would guess that the most likely location for this sketch was Hayhurst Point. It clearly is fall, with the yellow leaves on the birches and a few red leaves on perhaps some maple saplings. To me the light looks like morning - I think the alternate title Night Camp is probably incorrect. In fact, I can't think what in the sketch suggests night."

"I still think it is most likely a morning scene. It's easy to imagine Tom setting up his tent with the door facing east to enjoy the sunrise and morning light."

As explained in previous blogs, morning light is more likely to be pure white. After a day of wind and convection stirring up particles into the lower atmosphere, the afternoon light takes on a distinctly yellow tone. Rayleigh scattering of the blue component of white light out of the direct beam from the sun is responsible for this subtle transformation. People are generally, subconsciously in tune with such phenomena without thinking of it.

|

| Artist's Camp, Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park Alternate title: Night Camp Fall 1915 Oil on wood panel 8 5/8 x 10 11/16 in. (21.9 x 27.2 cm) Tom's Paint Box Size, Catalogue 1915.78 |

The trees also tell a tale, and my Thomson friend suggested several observations.

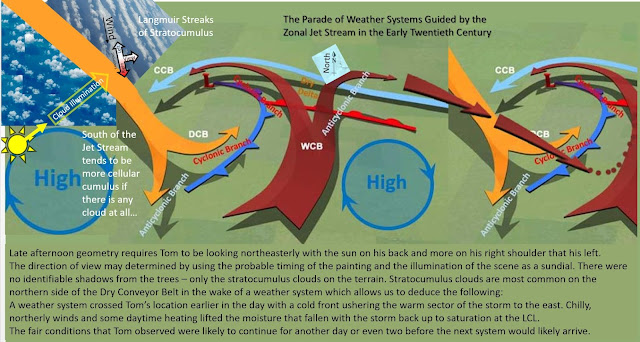

The illumination of the tent face and the extreme left edge of the trees can be combined with the orientation of the elongated band of altostratus. The following geometry results with the morning sun on Tom's left shoulder looking at the arch of a swath of stable cloud. The altostratus was likely associated with the anticyclonic companion of an approaching warm conveyor belt. Tom was looking westward. The winds were probably light. It would have been a great day to paint outside with no biting bugs.

|

| Horace Kephart, 1862-1931 |

Horace wrote: "the most suitable material is very closely woven stuff made from Sea Island or Egyptian cotton... the standard grade of 'balloon silk' runs about ... 5 1/2 oz (per square yard) when waterproofed with parafine. This trade name, by the way, is an absurdity: the stuff has no thread of silk in it, and the only ballooning it ever does is when a wind gets under it." Horace had a wonderful sense of humour as well.

Balloon silk was tightly woven and would shed the rain unless touched from the inside. Thankfully, modern tents have largely eliminated that problem!

As my Thomson friend also noted:

"Kephart talks a lot about outfitting for groups, but also more individual efforts, and includes contemporary information about everything related to camping and getting along in the woods. Interesting to read in 2024, and gives us a good idea about how things were more than 100 years ago. I think there is a lot that can give us some idea of Tom's equipment, food and camping experience..."

|

|

| Artist's Camp, Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park |

"At the office we had great arguments on the relative value of tents, fishing tackle, etc.; on anything to do with camping and woodcraft Tom was a master. He could pack his camping equipment, paints, etc. etc. into the smallest compass. He knew all about the best rods and flies for fishing. Indeed he eked out his small supply of cash by acting as guide up in the wilds of Algonquin. That he was an expert canoeist goes without saying. While the mosquitoes were singing outside his silken tent he would be painting some mood of nature from the inside."

|

| Artist's Camp, Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park |

Inscription recto:

- l.r., estate stamp

- l.l., estate stamp;

- label, Laing Galleries, Toronto;

- sketch of deer Thomson Collection @ Art Gallery of Ontario

Provenance:

- Estate of artist

- George Thomson, New Haven, Connecticut and Owen Sound, Ontario

- Laing Galleries, Toronto

- Father of J.S.D. Tory, 1951

- J.S.D. Tory, Toronto

- Montreal Trust Company, Executor of Estate of J.S.D.

- Tory Private Collection,

- Toronto Thomson Collection @ Art Gallery of Ontario

"The Wattie family has its own lore about Thomson. They joked about how he had, over time, become revered as an expert outdoorsman. 'He was not an expert canoeist,' says Copper. ' He hadn't even seen a canoe until he got to the park.' But Thomson was game and generous, and Wattie took him under his wing..."

"He was born in the summer of his 27th yearComing home to a place he'd never been beforeHe left yesterday behind him, you might say he was born againYou might say he found a key for every door..."