“

Bateaux” from the late spring of 1916 appropriately follows “

Sandbank with Logs”, "

The Drive“ and “

Abandoned Logs”. Tom Thomson, the Fire Ranger appeared to be following the loggers and chronicling the lumber industry of the early 20th Century.

|

Bateaux Summer 1916

Oil on wood 8 7/16 x 10 9/16 in. (21.5 x 26.8 cm)

Tom's Paint Box Size |

|

J.R. Booth and sons circa 1900

|

The three boats featured in Tom's painting were "

pointers". John R. Booth commissioned John Cockburn to build a solid boat to use as a working platform in the logging industry. John Cockburn had begun his boat-building business in Ottawa in the 1850s but moved it to Pembroke in 1859 after securing the Booth Contract. That strategic relocation saved transporting the finished pointers to his client 145 miles from Ottawa by horse and sleigh.

The Cockburns built their pointers to last at least ten seasons in normal use. Some boats only made it a few months due to the rocks and rapids of the Algonquin rivers. In peak years, the Cockburn family produced two hundred pointers! The historical boat was essential in the logging industry and was famed for being able to "float on a heavy dew".

The flat-bottomed wooden pointers were used in log drives to transport men and equipment to wherever they were required. In Tom's painting. the pointer was crewed by six men herding logs into a boom

Three generations of Cockburns built these famed and versatile boats. The business first passed to John's son Albert, and then, to grandson Jack. Jack Cockburn continued to produce pointers through to 1969 before he died in 1972. In recognition of the Cockburn family and the pointer's historical impact on the logging industry, a 32-foot steel replica of the pointer is displayed at the Pembroke marina.

The Pointer Boat business evolved into a hardware store under the name of Cockburn and Archer, who were still active into the 1980s. Cockburn and Archer Hardware Store even sold peaveys, the lumberman's metal-spiked lever with a pivoting hook called a cant hook attached.

J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris named this painting "Bateaux" when they met in the Studio Building in the spring of 1918. As detailed in the above graphic, the title is the French word for "boats" which described flat-bottomed boats throughout North America. The specific boats in Tom's painting and used in the Algonquin lumber industry were actually the locally crafted "pointers".

The arrangement of the pointers in this photograph from the Algonquin Park Archives is strikingly similar to the boats arranged in Thomson's painting. Even the distant hills bear a resemblance between the photo and the painting.

|

| The full image as provided by the Algonquin Park Archives& Collection - APM 2086 |

The flat bases and tops of the stratocumulus reveal the story behind those clouds. The uniform flat bases say that the sun heating the ground got those surface-based air parcels to the lifted condensation level (LCL). The flat tops shout out the story of a subsidence inversion.

The subsidence inversion can be explained using a Tephigram and was explained in "

What Goes Up ...". The following graphic uses the similar American National Weather Centre Skew-T Energy Diagram. Subsiding air becomes instantly unsaturated and warms quickly at the dry adiabatic lapse rate. The warmed layer becomes an impregnable lid for any thermals attempting to rise convectively from below. Clouds under a subsidence inversion have flat tops.

|

| The yellow star locates Tom in the Parade of Weather Systems |

At this point, I asked my friend and colleague Johnny Lade to take a look at this painting as if he were making a weather observation. Known to his students as "Johnny Met", he has a lifetime of experience observing the weather. Johnny nailed his observation since Thomson painted exactly what he saw.

"The thing about the painting is how everything stands out. The visibility looks CAVU (aeronautical meteorology term meaning "Ceiling And Visibility Unlimited") leading me to think that a cold front went through leading to a different brand of air. I think there is a conveyor belt above the clouds and the initial diurnal lift was cut off by a brisk geostrophic wind. The clouds are stratocumulus streeting lining up parallel to the winds. The visibility is so sharp I can almost see the leaves of the trees moving in the wind across the lake. The logs are acting like a breakwater with little or no wave action in the close-up. Whereas there seems to be wave action further out in the main part of the lake."

The "brisk geostrophic" winds that Johnny mentioned were the subsiding, anticyclonic companion of the dry conveyor belt depicted as the orange and white arrow in the above graphic. If you use your Coriolis Hand and curve your fingers in the same direction as the orange arrow, your thumb must point downward. Anticyclonically curved winds are also "super-geostrophic" in speed meaning the winds are stronger than the pressure gradient would suggest. The science behind this may be found in "Another Look at the Wind".

If Johnny had been there watching the actual clouds move on that day, he would have easily observed the drift of the clouds. Cloud motion would have revealed the wind direction and relative speed as well.

The cloud organization resulting from the interacting helical circulations of the wind and the surface-based convective thermals would have been fascinating to witness. The lower left portion of the above graphic attempts to explain those circulations in the atmosphere - essentially Langmuir Streak (see "

Langmuir Streaks – Take the time to Observe and Learn from Nature"). The gravity waves in the water surface used in that portion of the graphic must be perpendicular to the winds while the cloud streets parallel the flow. Linking the pieces of cloud in Tom's painting is a challenge from an earth-bound perspective. More than a century later, we can only apply the conceptual models to best explain what Tom might have seen.

Johnny also mentioned the "breakwater" effect of the log boom. The floating timbers bobbing up and down with any wave action would quickly dampen the energy of those incoming waves. Relatively calm matter must be found in the lee of any log boom. It would still be dangerous work walking those logs even with poles and spiked boots.

The colours of the landscape provide even more clues.

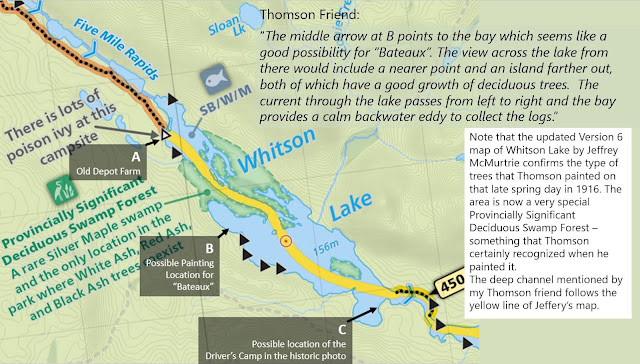

The last part of this story behind "Bateaux" is usually where we try to start the Creative Scene Investigation. Where was "Bateaux" painted? My Thomson friend may have found the answer just downstream from "Sandbank with Logs"!

"Whitson is an unusual lake, in that it is really just a widening of the (Petawawa) river. The shore is quite varied, with some rocky sections, some gravelly, and some sandbanks, while the islands are muddy silt. Most of the current passes along one quite deep channel while the rest of the lake is fairly shallow. The islands are damp with thick vegetation that seems out of place in the more northern landscape, and they are often flooded in the spring. I have seen no evidence of any kind to suggest that the lake was dammed at the outlet - it is contained by a rocky sill and during the spring high water has more than enough to float logs."

"I don't think the trees on the islands would have been aspen or birch - it would be too wet and muddy for them. Currently they are mostly covered with silver maples and other plants that prefer that sort of habitat."

It is vitally important to listen to one who knows and has been there! Following boots on the ground is often the only way to get to the truth. Note that silver maples leaf out in the spring very soon after aspen and birch and could easily explain the green patches that Tom painted!

Location "C" on the accompanying map is possibly the location of the historic photo of the Driver's Camp from the Algonquin Park Archives and Collection APM 2086. The distant terrain and the adjacent shoreline with the log is a convincing match as traced in the above graphic.

Comparing the topography Tom painted with the following Version 6 Whitson Lake area map by Jeffrey McMurtrie also reveals some interesting correlations. Letter "B" could be THE spot where Thomson sat while he observed the lumbermen at work on the log boom. The pale white arrows in the graphic enclose the view toward Hills 1 and 2. The blue and white arrow follows the flow of the back eddy into the shallow and protected bay.

Further investigation and paddling might be required to reach a definitive conclusion. Sometimes another letter other than "

X" marks the spot. Jeffrey McMurtrie has produced some terrific and educational maps ideal for hiking and canoeing in Algonquin Park. Visit "

Maps by Jeff" for the most recent version.

Hill 2 is one height contour taller than Hill 1 in Jeff's map but is noticeably stunted in Tom's painting. Hill 1 is a bit closer to the possible painting location but the height difference still seems a bit excessive. As my Thomson friend notes:

"I'm hoping it's just an angle of view thing, and when I get back to the actual spot I'll be able to sort it out. In the meantime, it's a good enough theory, and fun to think about, regardless."

May I digress for a bit more canoeing science? The sandy soils found in some localities along the Petawawa provide a blank canvas for the river and the Coriolis Force. The deep, main channel carved by the current and traced by the yellow line in the above map is deflected to the right when not restricted by terrain features. The anticyclonic back eddies that deflect to the right are typically larger than the cyclonic eddies to the right. The loggers even use that natural and larger deflection to collect timber harvest more easily. Your Coriolis fingers (right hand in the northern hemisphere) point in the direction that the logs are more apt to travel. Over eons, that flow has also deposited enough soil to support the Provincially Significant Deciduous Swamp Forest. If you are paddling with the current and wish to eddy out for a break, deflect to the right.

|

Bateaux Summer 1916

|

A prominent Canadian art historian once mentioned to me while I visited the National Gallery of Canada that Thomson would invent or distort compositional content to benefit the design. I did not truly agree with that assertion but perhaps artistic licence was used to make the hills slightly different in height and to create depth. The two hills are real in Jeff's topographical chart. Clear-cutting of the Algonquin forest could explain the drab springtime colours Tom painted on those slopes but not their stature.

I also wonder why the lone tall white pine on the left side of the panel was spared from the axe? Perhaps the swampy deciduous forest that is now deemed to be provincially significant just made that desirable tree too troublesome to harvest. We will never know for certain!

The more one investigates, the more questions come to light. Definitive answers might never be found leaving only probabilities and conjecture. One benefit of communicating this art and science in blogs is that the information can be readily updated should more information be discovered. The story can be a living and improving tale of authentication and learning.

The actual Creative Scene Investigation for "Bateaux" occurred in the order that it was written. Refinements on the tree identification and soil types can only be discovered by being there - "boots on the ground". Estimates based solely on the painting can easily be flawed and one needs to always be open-minded to suggestions and other possibilities.

Artistically, Tom loosely employed the "

Rule of Thirds" in "

Bateaux".The calm water in the lee of the log boom lies between the closest edge of the log boom and the upper gunwale of a pointer. The lowest third parallels these three lines. Meanwhile the upper third straddles the undulating horizon of the distant hills. The locations of the shocking stabs of colour do not relate to the intersection points of the thirds - something Tom also did in

Sandbank with Logs” and "

The Drive“.

Artistically, Tom was having fun capturing the activities of the lumbermen in action. The puzzle pieces of the Creative Scene Investigation all fit together.

Inscription recto:

- l.l., estate stamp (as applied by Harris and MacDonald)

|

| It was a daunting challenge to even attempt to name and date Tom's work. Lawren Harris and J.E.H. MacDonald were true friends of Tom! |

Inscription verso:

Inscription verso:

- c., estate stamp;

- l.l., in graphite, no. 48 Mrs. Harkness;

- c., in red pencil, 46;

- u.r., in graphite, W.C.L.;

- below stamp in graphite, G;

- (in 1970) inscribed on stretcher, in graphite, 5 Bateaux Rouges 48. Harkness? Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (853)

W.C.L. on the verso refers to Walter C. Laidlaw who may have considered buying the sketch.

Pointer boats were used mainly in the spring to guide logs down swollen rivers toward sawmills.

Provenance:

- Estate of the artist

- Elizabeth Thomson Harkness, Annan and Owen Sound

- Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (853).

- Gift from the Reuben and Kate Leonard Canadian Fund, 1927

This painting went to Thomson’s eldest sister upon his passing. Elizabeth's husband was Thomas “Tom” J. Harkness who was appointed by the Thomson family to look after the affairs of Tom’s estate. T. J. and Elizabeth lived in Annan, Ontario, just east of Owen Sound. From Elizabeth, aka "Mrs. Harkness", the painting went to the Art Gallery of Ontario where I first saw it - nose to nose. Funds from the Reuben and Kate Leonard Canadian Fund made that transaction happen in 1927.

|

| A Pointer entering the rapids in 1960 |

Many interesting stories can be discovered with boots on the ground, open minds and some science. History can be rediscovered and brought to life. As mentioned, this story might be fiction but the science is factual. Thank you once again to my Thomson friends and the Friends of Algonquin Park who maintain the Algonquin Park Archives.

May I also recommend "Late Summer 1916", a post by my friend known as "Tom Thomson's Last Spring". The story relates a personal side to the history of logging, fires and life in the bush that augments the brushwork of Thomson.

Warmest regards and keep your paddle in the water,

Phil Chadwick

No comments:

Post a Comment